Through this uncontrollably long post, I attempt to analyse the developments that have taken place in 2019 in India through some crucial Supreme Court judgments. I wish to thank Kishan Gupta for his valuable comments on the first draft.

Arbitrability of Disputes

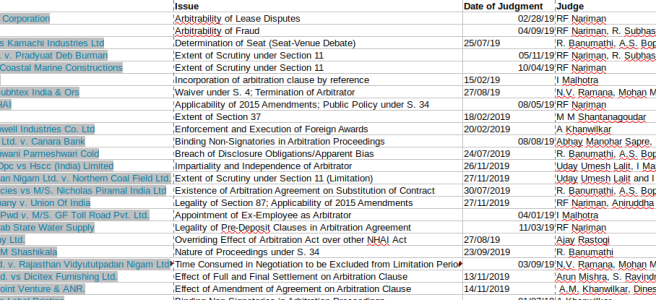

Largely governed by the principles pronounced in Booze Allen, India has, so far, followed a calculative approach towards arbitrability of disputes. Regarding tenancy disputes, Booze Allen had ruled that eviction and tenancy matters governed by special statutes can only be adjudicated by courts. The ruling in Booze Allen ran in line with an earlier Supreme Court judgment of Natraj Studios Ltd. v. Navrang Studios which had ruled out arbitration of lease disputes as they were to be adjudicated under special legislation and undermined public policy. Later, in 2017, Supreme Court was again faced with arbitrability of lease dispute in Himangi Enterprises v. Kamaljeet Singh Ahluwalia. This time the Court relied (rather erroneously) on the judgments in Booze Allen and Natraj Studios and ruled that lease disputes cannot be arbitrated irrespective of whether such disputes arose from special legislation. The judgment effectively left no scope for arbitrating lease disputes in India. In 2019, RF Nariman, in, Vidya Drolia v. Durga Trading Corporation, raised questions on the interpretation adopted by Himangi Enterprises. The Court clarified the ratio of Booze Allen and ruled that only those tenancy matters that (a) are governed by a special statute; (b) where statutory protection has been provided against eviction; (c) where jurisdiction has been solely conferred upon a special forum are non-arbitrable. Therefore, the judgment opens new pathways for arbitration of tenancy disputes which are governed by the Transfer of Property Act, 1882. The issue has been referred to a larger bench. Our editor, Shubhangi Agarwal wrote on this case here.

While some ruckus was created by contradictory judgments in N Radhakrishnan (2009) and Swiss Timing (2014), it seemed like the Supreme Court had settled the issue of arbitrability of fraud in Ayyasamy (2016). In Ayyasamy, the Court simply ruled that “serious allegations of fraud” were not arbitrable while “mere allegations of fraud” could be referred to arbitration. In doing so, the Court neither discussed the threshold required for an allegation to be ‘serious’ nor did it differentiate ‘mere allegations’ from the serious ones. This, of course, left abundant scope for interpretation and made it difficult to determine the arbitrability of a particular dispute. The principles enunciated in Ayysamy had to be clarified and Supreme Court, to some extent, did so in Rashid Raza v. Sadaf Akhtar. The Court brought two tests for identifying whether a dispute involving allegations of fraud was arbitrable, that is, firstly, whether the allegations permeated the entire agreement including the arbitration clause, rendering it void; or secondly, whether the allegations only affected the internal affairs of the parties and had no impact in the public domain. According to the Court, cases where the arbitration clause was not vitiated or the allegations did not affect matters in the public domain, the matter could be arbitrated.

For greater insights into the decision, visit here and here.

Pre-Arbitration Judicial Interference under Section 11

The extent to which courts can delve into the question of the existence of an arbitration agreement has been extremely contentious in India. We have seen a roller-coaster change in the regime from Konkan Railway (2002) to Patel Engineering (2007) up to the 2015 Amendment. Even after the 2015 Amendment, Supreme Court has been juggling between different approaches towards the standards of scrutiny to be done while dealing with an application for appointment of an arbitrator or while referring parties to the arbitration. Initially, in Duro Felguera (2017), it was held that courts were required to see only the existence of arbitration agreement – “nothing more, nothing less”. The Court also determined the factors for deciding the ‘existence’ of an arbitration agreement. In its opinion, it was needed to be seen that the agreement contains a clause which provides for arbitration pertaining to the disputes arising between the parties to the agreement [emphasis supplied]. Hence, the Court included ‘scope’ of the agreement in its ‘existence’ determination. Later, in March 2019, in United India Insurance v. Antique Art Exports, the Court ruled that the pre-condition for invoking arbitration was not met which rendered the arbitration clause ineffective and incapable of being enforced. On one hand, many consider the approach in United India to be in contravention with that in Duro Felguera, others believe that it followed Duro’s dictum which included enquiry of ‘scope’ as a factor to determine existence. It held that appointment of arbitrator allowed the Courts some degree of judicial intervention. In a similar fashion, the Supreme Court in Garware Wall Ropes v. Coastal Marine Constructions and Engineering Ltd while dealing with a matter under Section 11 went on to ascertain whether the arbitration agreement was duly stamped that is, it went on to determine the ‘validity’ of an arbitration agreement as opposed to its ‘existence’. In the Court’s opinion, determination of existence included ‘de jure’ existence of the agreement. In sum, the Court seemed to be tangled up between ‘existence’ of an agreement and its ‘validity’.

The judgment of the single judge bench in United India Insurance was later overruled by a three-judge bench Supreme Court in Mayavati Trading Pvt Ltd v. Pradyuat Deb Burman where the Court ruled in the post-2015 Amendment regime owing to Section 11(6A), courts were not required go further than determining existence of the arbitration agreement i.e. issues such as whether accord and satisfaction had taken place were not supposed to be determined by the Court during the Section 11 proceedings. Mayawati Trading relied upon Duro Felguera to reach its conclusion but it seems to have omitted Duro Felguera’s inclusion of ‘scope’ in the determination of ‘existence’. Nevertheless, the decision in Mayavati Trading was followed by another pro-arbitration ruling in Uttarkhand Purv Sainik Kalyan Nigam Ltd. v. Northern Coal Field where the Court ruled that the arbitral tribunal, and not the courts, during the appointment stage, were the right forum to decide on the issue of limitation. The judgment is laudable but the Court seems to have employed an incorrect interpretation of the previous ruling of IFFCO v. Bhadra Products to rule that issue of limitation must be dealt with by the tribunal.

After the 2015 Amendments came into being, it was predicted that the Section 11 conundrum would be settled forever. However, the Supreme Court, at times, has proved us wrong with some surprising and perhaps, undesirable rulings. While, Mayawati Trading and Uttrakhand Kalyan Nigam progress in the right direction, both the judgments either leave scope for further clarification or are riddled with errors. With this being the case, pre-arbitral judicial interference in India remains into muddy waters.

For a more in-depth discussion on these cases, visit the following links:

United India Insurance: here

Mayawati Trading: here

Uttrakhand Purva Sainik Kalyan Nigam: here

Seat-Venue Debate

Identification of seat in the so-called ‘pathological arbitration clauses’ has proved to be a difficult task for the courts. Given the ‘error’ made by BALCO (2012) regarding exclusive jurisdiction of the seat court and followed by the nullification of Section 42 in the Indus Mobile (2017), such determination becomes more problematic in domestic arbitrations. In 2019, the Supreme Court grappled with the seat-venue determination in the context of domestic arbitration. Firstly, in Brahmani River Pellets Ltd. v. Kamachi Industries Ltd, the Court interpreted an arbitration agreement that read as: “Arbitration shall be under Indian Arbitration and Conciliation Law 1996 and the Venue of Arbitration shall be Bhubaneswar”. According to the Court, in absence of any other indication, the ‘venue’ shall be considered as the seat of arbitration. While the decision of the Court is not problematic, the wording probably is. In its reasoning, the Court says, “considering the agreement of the parties having Bhubaneswar as the venue of arbitration, the intention of the parties is to exclude all other courts”. The judgment has received criticism as it does create confusion by diluting the difference between ‘venue’ and ‘seat’ of the arbitration.

The confusion created by Brahmani River Pellets was cleared, to a huge extent, in BGS SGS Soma JV v. NHPC Ltd. In BGS Soma, there was another peculiar arbitration clause which provided that: “arbitration Proceedings shall be held at New Delhi/Faridabad”. In a sizeable judgment, the Court produced several methodologies to be followed while determining seat. First, wherever ‘venue’ is mentioned in relation to ‘arbitration proceedings’ in a contract, the ‘venue’ would be considered as the ‘seat’ of arbitration so long as there is no other contrary indicia. Second, in case of international arbitration, arbitral rules chosen by the parties would be considered as significant indicia that the ‘venue’ would be the seat of the proceedings so long as such arbitral rules are unique to the ‘venue’. The Court also held that Hardy Exploration (2018) which had ruled that ‘venue’ can become ‘seat’ ‘if something else is added to it as concomitant’ to be incorrect. Further, the Court placed reliance on BALCO and the earlier England and Wales HC judgment in Roger Shashoua (2009). Similarly, Delhi High Court’s decision in Antrix Corporation (2018) was also held to be incorrect. BGS SGS Soma is an important ruling as it brings the basic methodologies to determine seat back into practice. While some of the approaches may be fact-oriented, the judgment also brings a much-needed clarity on paragraph 96 of BALCO.

For more on BGS Soma, visit these blogs.

Impartiality and Independence of Arbitrators

Supreme Court in 2019, once again, exhibited its mixed approach towards securing impartiality and independence in arbitration proceedings. In January 2019, the Court rendered its opinion on the validity of appointment of an ex-employee as an arbitrator in The Government of Haryana Pwd v. M/S G.F. Toll Road Pvt. Ltd. While the case belonged to pre 2015-amendment regime, the Court relied on Entry 1 of Fifth Schedule and held that ex-employees were not covered under it. Consequently, the objections on impartiality and independence of the arbitrator were dismissed. We covered this case here. Later, in Bharat Broadband Network Ltd. v. United Telecoms Ltd, the Court had the opportunity to interpret the newly inserted proviso to Section 12(5). The proviso to Section 12(5) provides the parties with the right to waive the applicability of standards of impartiality and independence by agreement after the dispute has arisen. In Bharat Broadband Network, the Court highlighted that such an agreement must be expressed in writing and cannot be inferred by conduct that is, parties cannot be deemed to have ‘waived’ the standards of impartiality and independence under the proviso. One of the essential requirements for raising the issue of partiality as a ground to set aside is that the party should raise the challenge before the tribunal during the proceedings. This issue was addressed by the Court in Vinod Bhaiyalal Jain v Wadhwani Parmeshwari Cold Storage Ptv Ltd where the Court upheld the notion of ‘reasonable apprehension of bias’. In reference to the facts of the case, the Court noted that the objection raised before the tribunal were extremely vague and hence, could not constitute a valid challenge.

Lastly, with respect to unilateral appointments, the Court followed the law laid down in TRF v. Energo. In Perkins Eastman Arhitects DPC v. HSCC (India) Ltd., the Court was again faced with a government contract which provided for the unilateral appointment of arbitrator. With an approach that is heavily inclined towards saving the interests of the other party to the arbitration, the Court held that a person having an interest in the dispute is not only ineligible to be an arbitrator, he is also ineligible to appoint anyone else as an arbitrator. The Court did clarify that this position was only with respect to the appointment of a sole arbitrator. A direct consequence of Perkins is that the unilateral appointments in India are no longer valid in case of a sole arbitrator.

For more on Vinod Bhaiyalal Jain and Perkins Eastman, visit these links.

Post-Award Judicial Interference

After the 2015 Amendments, Courts have followed the policy of minimal judicial intervention with respect to setting aside of awards. However, with respect to ‘public policy’, interpretation of terms such as ‘fundamental policy of Indian law’ and ‘patent illegality’ remains controversial. In the decisions of Western Geco (2014) and Associated Builders (2014), the Court expanded the meaning of ‘fundamental policy of Indian law’ which proved undesirable from an arbitration perspective. When the Supreme Court dealt with the interpretation of ‘public policy’ in Ssangyong Engineering and Construction Co. Ltd. v. NHAI, it solved the problems created by the foregoing rulings by restricting the interpretation of the ‘fundamental policy of Indian law’ to desired limits. The Court ruled that violation of principles of natural justice was suited as ground under ‘most basic notions of morality or justice’ and not ‘fundamental policy of Indian law’. With respect to the former, the Court observed that the interpretation made by Associated Builders was an apt one but added that the ground dealing with ‘morality or justice’ should only be entertained where the breach in the award shocks the conscience of the Court. In a similar vein, the Court opined the insertion of ‘Wednesbury principles of reasonableness’ in ‘public policy’ opens floodgates. Accordingly, the Court considered it to be more appropriate in the ‘patent illegality’ ground. Further, it clarified that ‘patent illegality’ is to be understood as such illegality which ‘goes to the root for the matter’ and ‘appears on the face of the award’. The Court further ruled that a mere contravention of a statute not linked to public policy does not amount to ‘patent illegality’. While the Court did set aside the majority award on the ground of that it was in conflict with ‘basic notions of justice’, it stressed that the ground should be invoked in exceptional circumstances only and the Courts must restrain from entering into the merits of a dispute. Interestingly, the Court used its extraordinary power under Article 142 of the Constitution and upheld the minority award. We have covered Ssanyoung in detail here and here.

Continuing the pro-arbitration approach, the Court, in Canara Nidhi Ltd. vs M. Shashikala, the Court reaffirmed the view that Section 34 proceedings are summary in nature. Based on the 2019 Amendments to Section 34 that require a party to establish ‘on the basis of the record of the Arbitral Tribunal’ as opposed to evidence that was not produced before the tribunal, the Court held that a party cannot adduce evidence during Section 34 proceedings. Visit this blog post for greater insight into the decision.

A similar approach was adopted with respect to Section 37. In MMTC v. Vedanta Ltd, the Court ruled that the grounds enumerated under Section 37 were extremely restrictive in nature and any assessment under it should be limited to the grounds laid down during the Section 34 proceedings, that is, if a party has failed to raise a ground during the Section 34 proceeding, he cannot introduce that ground during Section 37 proceedings. We discussed this judgment in detail on our blog.

In another interesting ruling, the Court in LMJ International Ltd v. Sleepwell Industries Co. Ltd reiterated that there should be a narrow interpretation of Section 48. It added that in enforcement proceedings cover the issues of execution as well. In a remarkable fashion, the Court imposed an unusual cost of USD 30,000 against the party trying to resist the award for causing delay in enforcement.

Applicability of 2015 Amendments

Applicability of 2015 Amendments had been a controversial issue ever since the amendments came into effect. Following a literal interpretation of Section 26 of the 2015 Amendment Act, the Supreme Court in BCCI v. Kochi had ruled that the Amendments were applicable on the arbitration proceedings commencing on and after Oct 23, 2015, and court proceedings commencing after Oct 23, 2015, regardless of the fact that the corresponding arbitration proceedings in such court proceedings were initiated before the foregoing date. However, with respect to Section 36, the Court held that the amendment (which removed ‘automatic stay’ on the award) shall be applicable even if the court proceeding has been filed before Oct 23, 2015. The exception for Section 36 finds its roots in the differentiation made by the Court between substantive and procedural amendments. The Court opined that the amendments brought under Section 36 were procedural in nature and therefore, could be applied retrospectively. Court’s interpretation of Section 26 of the Amendment Act was followed in Ssangyong Engineering & Construction Co. Ltd. vs National Highways Authority of India. In Ssangyong, the Court classified the amendments made under Section 34 as clarificatory but acknowledged that the amendments had brought significant substantive changes. The established rule on clarificatory amendments lays that such amendments can be retrospectively applied barring where the clarification is of such nature which brings substantive changes. Following the jurisprudence, the Court ruled that amendments made under Section 34 were prospective in nature. The Court also followed the approach adopted in BCCI v. Kochi. Later, when 2019 Amendments came into effect, the legislature overruled BCCI by inserting Section 87 into the Act. Contrary to the ruling in BCCI, Section 87 provided that the 2015 Amendments were to only apply on those court proceedings which were initiated after October 23, 2015, with corresponding arbitration proceedings initiated only after the said date i.e. it shall not apply to those court proceedings which commenced after Oct 23, 2015, but where the corresponding arbitration proceedings were initiated before the foregoing date. The new provision ran in contradiction to Section 26 of the 2015 Amendment Act and reduced the scope of application of 2015 Amendments. This also meant that the erstwhile Section 36 which provided for ‘automatic stay’ on awards would continue to apply on all the awards that resulted out of arbitrations commencing before Oct 23, 2015. These developments culminated into a constitutional challenge against Section 87 in the Supreme Court in Hindustan Construction Co. Ltd. v. Union of India. A three-judge bench of Supreme Court held Section 87 to be “manifestly arbitrary and unconstitutional”. With respect to the amendments made under Section 36, the Court held that it was unreasonable to allow arbitral awards to be ‘automatically stayed’ during the Section 34 proceedings as such proceedings are seldom successful due to the restrictive nature of the provision and are often used simply to stop the award creditors from getting the benefits of the award. In the opinion of the Court, Section 87 undermined the purpose with which the legislature had made amendments to Section 36. We covered Hindustan Construction here.

Although, these rulings have probably solved the puzzle of applicability of 2015 Amendments, the whole saga starting from inconsistent High Court rulings which seemed to have been settled in the BCCI vs Kochi judgment to the introduction of Section 87 and its expulsion in Hindustan Construction paints a dazed image of Indian arbitration regime before the global community. Indian regime has often suffered from lack of cohesion between judiciary and legislature on arbitration and this saga has shown us that the problem may not be completely solved yet.

Non-Signatories to an Arbitration Agreement

Arbitration often operates in a complex corporate network where a relevant party may not be a signatory to the arbitration agreement. To ensure that entities do not escape arbitration proceeding simply because they were not a signatory to the agreement, ‘Group of Companies’ doctrine was borrowed in arbitration. Initially recognised in Dow Chemicals, Indian courts have employed the doctrine to bind non-signatories. In 2019, there were two major decisions with respect to non-signatories. In Reckitt Benckiser (India) v. Reynders Label Printing India, the Court proceeding to apply the test laid down in Cheran Properties and ultimately held that the non-signatory did not have a causal connection with the process of negotiations preceding the Agreement or the execution of the Agreement.

A month later, in MTNL v. Canara Bank, the Court was faced with the question of whether a subsidiary was bound by the arbitration agreement entered into by its parent company. Although the ruling in MTNL is similar to Reckitt Benckiser, it is less fact-oriented and has more to offer in terms of jurisprudence. The Court observed a few things: firstly unless acting in the capacity of an agent, entering into an agreement by the parent company will not bind the subsidiary company to it and vice-versa. Secondly, a non-signatory can be bound by an arbitration agreement via Group of Companies doctrine where a clear evidence of parties’ intention to bind the non-signatory is present. Lastly, the Court held factors such as the relation between the non-signatory and signatory, the commonality of the subject-matter and the nature of the transaction, to be important while ascertaining whether a non-signatory was bound to an arbitration proceeding.

A detailed account of both cases can be found here.

Miscellaneous

There were several notable rulings in other issues that deserve attention. Government contracts often refer to guidelines, circulars etc. for referring arbitration clauses in the contract. In Giriraj Garg v. Coal India Ltd., a reference from 2007 Coal Scheme was challenged. The Court followed the law laid down in MR Engineers (2009) which was later expanded in Inox Wind (2018), where the reference is in standard form contract, the incorporation would be valid. The Court declared the 2007 Coal Scheme to fall in the aforementioned category and allowed incorporation. The judgment may evoke pro-arbitration sentiments but may be undesirable from the perspective of commercial bodies contracting with the government. In the present case, the arbitration clause provided that contract would be governed by “Guidelines, Circulars, Notices, and Instructions issued by Coal India Ltd., Bharat Coking Coal Ltd. etc”. Such a wide reference should not be read as valid incorporation as it undermines the consent of the other party to the arbitration. We covered Giriraj Garj on our blog here.

In another matter that involved government contracts (National Highways Authority v Sayedabad Tea Company), the issue was whether mechanism for appointment of arbitrator in the Highways Act overrides the one present in the 1996 Act. In an earlier concluded ruling (NHAI v. Prakash Chand (2018)), the Court had held that the Highways Act was special legislation and that it had an overriding effect regarding the determination of compensation. Similarly, in Essar Power Limited (2008), the Court had ruled that provisions of dispute resolutions in the Electricity Act had an overriding effect over Section 11 of the 1996 Act. While the Court has also held the 1996 Act as special legislation, it followed the aforementioned rulings to rule that Highways Act would override the provisions in Section 11 of the 1996 Act. The case has been covered elsewhere in more detail.

Disputes often arise after novation or alternation of contracts. In such cases, the existence of the arbitration agreement can be a controversial issue where the new or the amended contract does not contain the agreement. As usual, the Supreme Court had made a few significant ruling in this aspect. In Zenith Drugs And Allied Agencies v. M/S. Nicholas Piramal India Ltd, a dispute arose after the parties had got a compromise deed which had substituted the original contract. The Court analyzed the language of the deed and ruled that the arbitration agreement in the original contract had been substituted and hence, the compromise deed was not arbitrable. The Court reached an identical conclusion in Wapcos Ltd. vs Salma Dam Joint Venture as the parties had signed ‘Amendment of Agreement’ which substituted the agreement.

Conclusion

2019 may be as significant as 2015 in terms of the sweeping changes brought to the regime. With respect to these judicial decisions, we can be certain of a few things. It seems obvious from the developments in the post-award phase that the judiciary is attempting to support the arbitration system and uphold its legitimacy. At this juncture, it must be stressed that a straitjacket liberal approach towards arbitration may not always further the objectives that arbitration, as a means of dispute resolution, seeks to achieve. Nevertheless, the situation with respect to pre-arbitral judicial interference remains uncertain and the conflicting rulings do not help it. It will be interesting to observe the approach of the courts when the new procedure for appointment of arbitration as envisaged in the 2019 Amendment comes into effect.

(Parimal serves as a Contributing Editor of the RMLNLU SEAL Blog. He may be contacted at parimalkashyap97@gmail.com.)

I truly liked reading your post. Thank you so much for taking the time to share such a nice information. You can also visit https://www.legalprofessionals.in

LikeLike